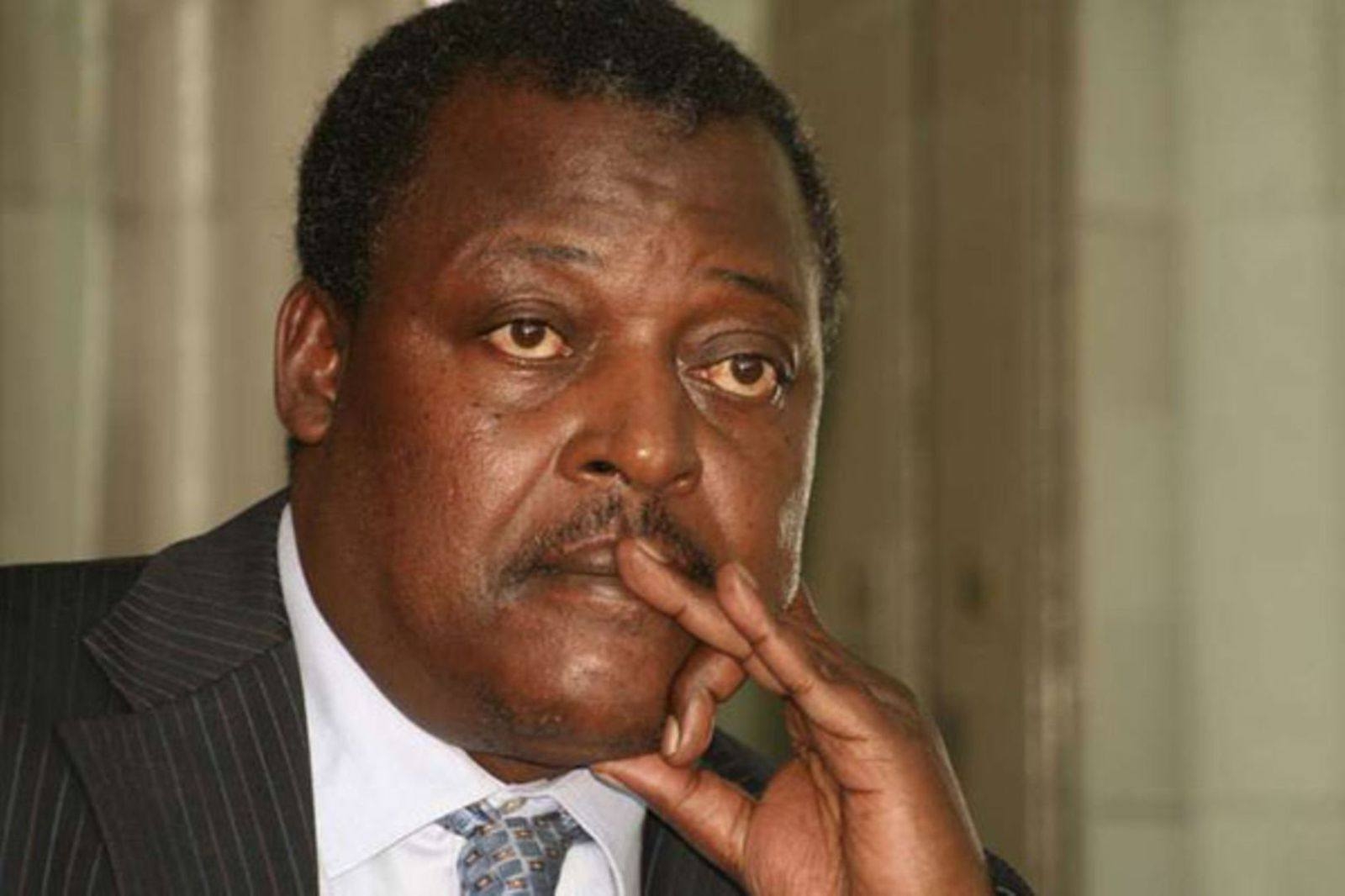

The recent explosion of a civil war in Sudan is only the symptom of deep-rooted problems the African state faces. On its surface, the civil war has been portrayed as a rivalry between two generals. General Abdel Fattah al Burhan and the leader of the Rapid Support Forces, General Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo.

However, a closer review reveals colonial and regional pressures, in addition to a deficit of democracy, that have led to an implosion of the state in Sudan. Here is why Sudan’s civil war is more than a rivalry between two generals.

The colonial legacy created a marriage of the unwilling. Some regions did not want to be a part of independent Sudan on January 1, 1956. Over time, these pressures have resulted in a brutal 22-year civil war that resulted in the divorce of South Sudan from Sudan on July 9, 2011.

Sudan’s borders were further threatened by separatist elements in the Darfur region, South Kordofan and the Blue Nile. In addition to this, there is an ongoing dispute between Sudan and South Sudan over the Abyei region. These regional conflagrations only added to the already volatile security and military situation in Sudan where the two generals mobilised armed forces to back their effort to gain power.

Secondly, regional powers continue to make the civil war in Sudan even more lethal. These regional powers include Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Because the regional powers do not directly suffer the bombing of their cities and civilian deaths, they have a reduced incentive to stop supporting the two factions in Sudan.

In this regard, Egypt and Israel have aided the al Burhan faction of the army. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been more sympathetic to the RSF faction. This has resulted in both generals being used as proxies in the civil war in Sudan to advance the interests of regional powers keen on gaining leverage over the state of Sudan.

Lastly, since independence, Sudan has suffered from a deficit of democracy in its institutions. It has never had a democratic culture, a history of free and fair elections or a peaceful handover of power from military to civilian regimes.

The militaristic nature of the politics of the state in Sudan ensures the military is not subject to civilian control. It is deeply entrenched as an extractive agent of the largesse of the state, to benefit elites in the military.

In addition to this, the current stalemate between General al Burhan and General Hemeti illustrates the fragile nature of Sudanese politics. Al Burhan led a military coup that truncated the military’s power-sharing with civilians.

This civil war has broken out because of the uncertainty of how to integrate the RSF into the Sudanese army. Both al Burhan and Hemeti fear being held accountable for past actions of commission and omission by a popularly elected civilian administration once the army is fully integrated and demands are made for a transition to civilian rule.

There's also the issue of accountability around looting of the state coffers and brutal executions of pro-democracy demonstrators in the months leading to the collapse of the Bashir administration and after.

Former President Omar al Bashir was never keen to hand power to civilians. Neither are al Burhan or Hemeti. As a result, the civil war in Sudan will only get worse before it gets better.

There is a distinct possibility the Darfur region from where Hemeti hails, will demand to break away from Sudan and declare its independence. The tragedy of the conflict is that the winner of the war will be the loser. Sudan will have lost. Things do not look good for Sudan.

Lecturer, City University of New York