A vaccine could offer a cost-effective path to a post-HIV pandemic future. It could markedly reduce the number of new infections lessen the number of people requiring lifelong treatment.

Over the past 20 years we have seen great progress in the HIV response; as of 2024 more than 30 million people were accessing antiretroviral treatment, accounting for more than 76 per cent of all those who need care around the world.In Kenya, more than 97 per cent of people living with HIV have been initiated on treatments that are able to extend their lives and prevent them from transmitting the virus to others. This has contributed to an 80 per cent reduction in the number of new infections reported annually over the past 15 years.

Sustained investments in the HIV response through the United States President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (Pepfar), The Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria and other governmental and non-governmental initiatives have enabled incremental success over the past two decades.

The shift in priorities away from supporting the Pepfar programme and the changing landscape for provision of global aid presents new risks including the possibility of interruptions to care and treatment programs and reduced availability to currently recommended prevention methods. This has the potential to destabilize the global HIV response. New strategies led by national governments and regional bodies will be necessary to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable people around the world continue to be met.

In addition to ensuring the continuity of care and treatment programs, ensuring effective options for the prevention of HIV are available is more important than ever. In addition to condoms, voluntary medical male circumcision and daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drugs, there are several long-acting PrEP products that have shown remarkable results: trials of injectable lenacapavir, for example, have shown nearly 100 per cent efficacy in preventing HIV when the drug is administered every six months.

We need this and other new tools, including cabotegravir, a bimonthly injectable, and the dapivirine vaginal ring, to be made available to individuals and communities vulnerable to HIV around the world.

In order to progress beyond control of the HIV pandemic towards elimination of HIV as a public health threat, an effective vaccine that can provide durable immunity to wide portions of the population will be required. New evidence is demonstrating that we are on the right path in the development of a HIV vaccine.

Recent scientific breakthroughs have increased knowledge of the virus and how it interacts with the human immune system. Scientists at IAVI and our partners are currently testing a novel approach called germline-targeting vaccine design which has shown significant promise.

This approach coaches the immune system to generate broadly neutralising antibodies (bnAbs), which hold the potential to prevent HIV acquisition and overcome the virus’ defence mechanisms. The identification of bnAbs has given us a target for vaccine development, enabling the development of a roadmap for vaccine design.

In addition to shoring up our HIV prevention, care, and treatment programmes, we must continue to support research into the new tools that can eventually bring the HIV pandemic to a permanent end.

A vaccine could offer a cost-effective path to a post-HIV pandemic future. The opportunity to provide long-term immunity could markedly reduce the number of new infections lessen the number of people requiring lifelong treatment. This intervention could help manage the mounting costs and ensure that HIV interventions implemented through national programs are sustainable over time.

Scientific advances, including vaccine development, can take place on a longer time horizon than any of us would prefer, but these efforts can bear remarkable fruit. It took scientists over two decades to develop the polio vaccine, which has today driven us towards eradication of the virus. With HIV vaccine development we are also playing the long game. If we press on with HIV vaccine development, we will indeed someday look back on HIV as a pandemic of the past, relegated to history.

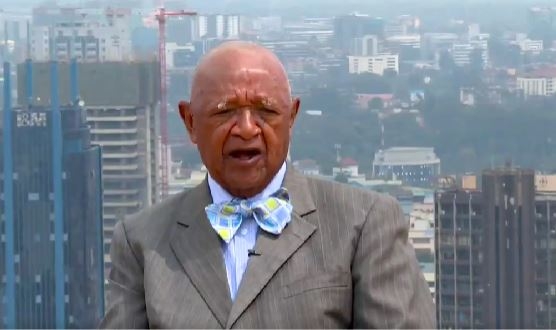

Dr Vincent Muturi-Kioi leads IAVI’s efforts to develop an HIV vaccine. He has worked in vaccine development for over 16 years and is based in Nairobi.