Coding and

Robotics Student Diramu Galgallo showcases her completed project of an

ultrasonic sensor-equipped Arduino-powered obstacle avoidance car at Karare AIC

CDC Primary School./STEPHEN ASTARIKO

Coding and

Robotics Student Diramu Galgallo showcases her completed project of an

ultrasonic sensor-equipped Arduino-powered obstacle avoidance car at Karare AIC

CDC Primary School./STEPHEN ASTARIKO Coding and

Robotics Student Diramu Galgallo showcases her completed project of an

ultrasonic sensor-equipped Ardiuno-powered obstacle avoidance car at Karare AIC

CDC Primary School./STEPHEN ASTARIKO

Coding and

Robotics Student Diramu Galgallo showcases her completed project of an

ultrasonic sensor-equipped Ardiuno-powered obstacle avoidance car at Karare AIC

CDC Primary School./STEPHEN ASTARIKO

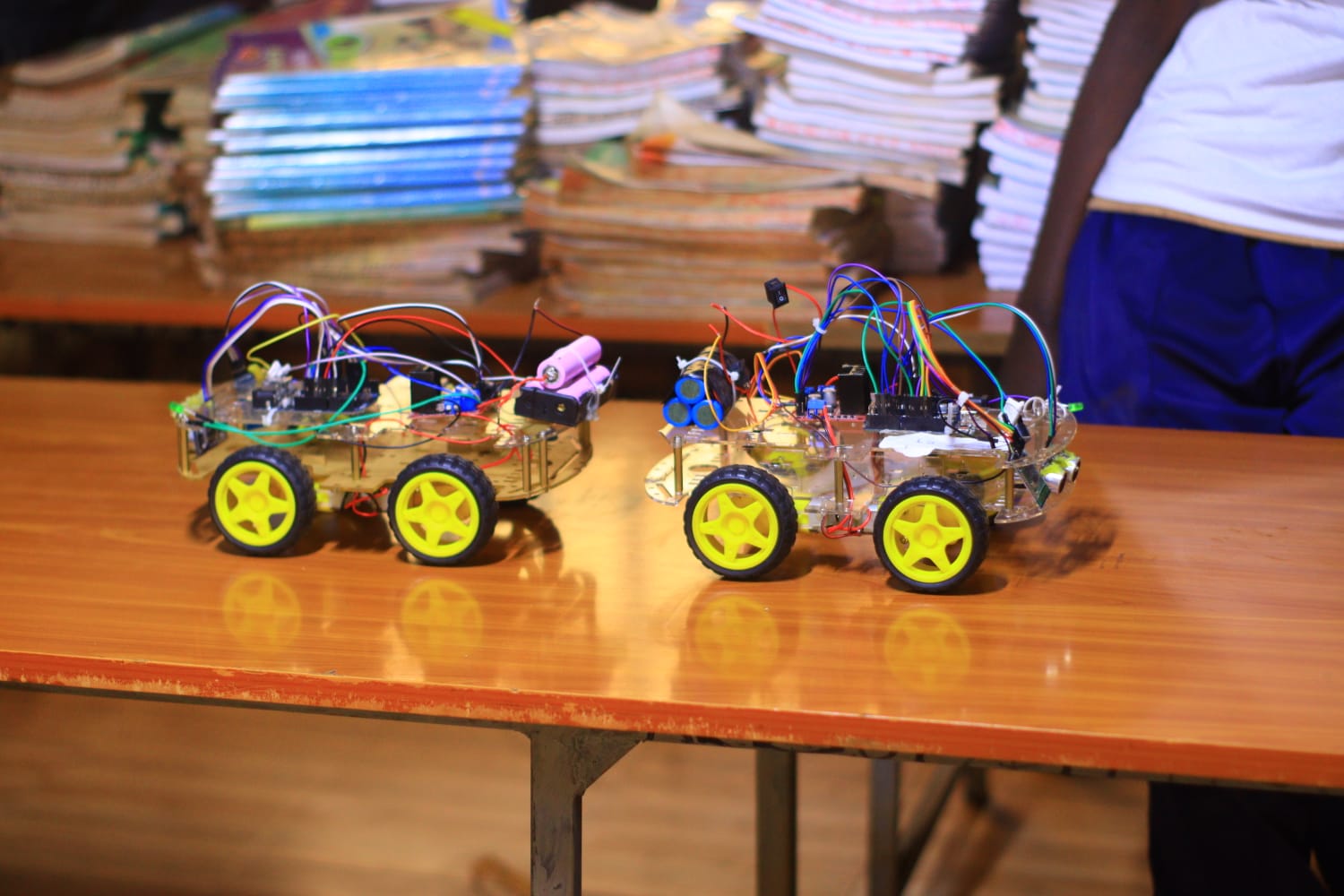

Arduino-powered obstacle-avoidance cars made by learners at Karare AIC CDC school in Marsabit./STEPHEN ASTARIKO

A quiet transformation is unfolding at Karare AIC CDC Primary School in Marsabit.

In a county better known for its dry plains and pastoralist life, young learners are discovering that coding and robotics can unlock futures far beyond the dusty horizon.

Inside the classrooms, where goats graze just beyond the

windows, children are proving that the next generation of African engineers may

rise not from wealthy capitals or global tech hubs, but from schools in Kenya’s

arid North.

Eleven-year-old Diramu Galgallo proudly showcases her Arduino-powered obstacle-avoidance car, complete with ultrasonic sensors.

“If the Kenyan government adopted this system, it could reduce road accidents across the country. Every car should have sensors to save lives,” she says with striking conviction.

Her invention mirrors real-world autonomous driving technology—living proof that even in one of Kenya’s most underserved counties, children can design innovations with global relevance.

For pastoralist families, such ingenuity carries an even deeper significance. Another group of pupils has built a motion-sensor alarm for cattle pens, a potential lifeline against the constant threat of cattle rustling.

“Robotics isn’t here to replace us—it enhances us. Early coding fosters logical thinking, creative problem-solving, and teamwork,” explains tutor Enock Nzioka, watching his pupils programme their creations.

The robots themselves are modest—plastic kits, wires, and tiny circuit boards—but their meaning is profound. In homes where many have never owned a computer, children are learning to speak the language of machines, to think in algorithms, and to imagine possibilities once thought unreachable.

The initiative is driven by Pawa Tech director Clifford Otieno, who runs sessions during evenings and holidays. He has already trained more than 140 students aged four to 12, and he delights in a surprising trend:

“More girls than boys are pursuing robotics here,” he notes with pride.

For teachers like Samuel Oduor, coding is more than technical skill—it is cultural.

“Coding is like a language. The same way these children grow up speaking Borana, Swahili, and English, coding allows them to communicate with machines.”

Still, progress faces hurdles. Robotics kits are expensive to import, spare parts are scarce, and power outages sometimes stall sessions. Yet the change is undeniable.

Joseph Duba of Compassion International reflects on the journey:

“Growing up here, we never even saw a computer. Now, we are training children from the poorest households to become tomorrow’s technologists.”

Beyond robotics, children are also experimenting with animations, games, and interactive stories through drag-and-drop coding tools like Scratch.

“It gives them freedom to express themselves. They’re tinkering, solving problems, and building confidence,” Oduor says.

These efforts align with national reforms. Under the Competency-Based Education, coding is now formally recognised, echoing Africa’s broader vision of building a digital economy.

Trainer Martin Mungai from CEMASTEA believes the ripple effect could be transformative. “If every household had a coder, Africa could actively participate in the digital economy.”

That dream may be closer than many think. Against the odds, Marsabit has already produced its first generation of coders and robotics enthusiasts—children whose families live far from fiber optic cables and Nairobi’s tech hubs.

Local scientist Hassan Guyo, inventor of JangaVoice, an early-warning climate app, sees their progress as proof that innovation thrives anywhere.

“AI is the canvas and human creativity is the brush. When we

merge automation with imagination, we paint a future of endless possibilities—where

technology enhances rather than overshadows our lives.”

His colleague Somo echoes the urgency of inclusion. “There is a need to democratise learning early and empower communities to co-create solutions.”

And so, with robots, code, and unrelenting curiosity,

Marsabit’s children are rewriting their story—one blinking sensor at a time.

INSTANT ANALYSIS

The Marsabit coding and robotics story is more than a feel-good education piece—it highlights a profound social shift. In a region long defined by poverty, drought, and marginalisation, children are embracing technology that could redefine their community’s future. Their inventions are not abstract; they tackle real local challenges like cattle rustling and road safety. The fact that girls are leading in robotics defies gender stereotypes and signals cultural change. However, sustainability remains fragile due to high costs, poor infrastructure, and limited government support.