When the first group of Kenyan officers touched down in Port-au-Prince on June 24, they landed not at an airport but in a war zone.

The tarmac had fallen silent long before their arrival, overtaken by lawless gangs that had seized Haiti’s most strategic installations.

Two Formed Security Units (FSUs), one from the General Service Unit and another from the Border Patrol Unit, had spent 10 weeks preparing for what President William Ruto described as a “mission for humanity”.

Yet, nothing in their training fully prepared them for the reality on the ground: an airport where aircraft could not land; a seaport blocked by barricades; a capital city paralysed; and institutions, hospitals, police academies and military training schools reduced to gang territories.

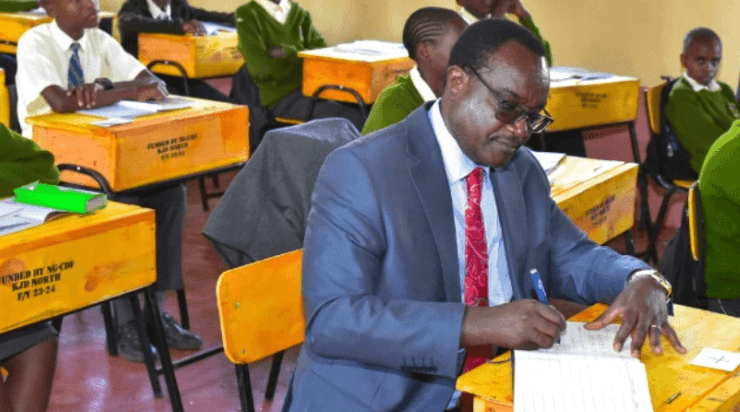

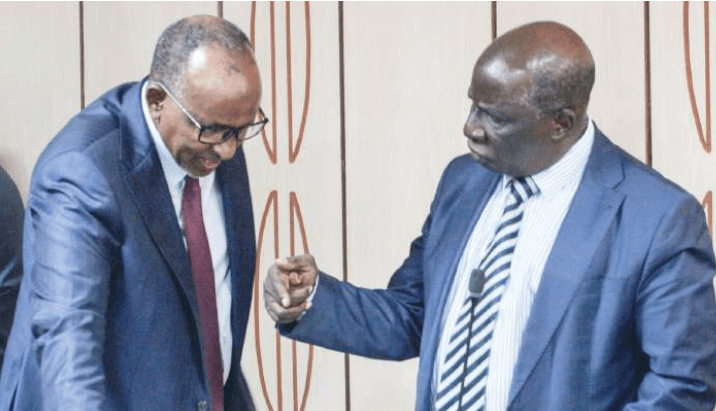

At a luncheon and debriefing at Embakasi A Campus a day after their return, Senior Superintendent of Police Mwinga, provided a detailed account of the 17 months Kenyan officers spent stabilising a country that had lost control to heavily armed militias.

He traced the mission from the landing to the final days when Haiti’s major institutions had been reclaimed and thousands of civilians could move, work and farm again.

Upon arrival, officers found Forward Operating Bases (FOBs) were non-existent and the airport had been fully occupied by gangs.

With no time to lose, the Kenyan contingent executed what is known in combat operational circles as a “hot landing,” touching down directly in hostile territory to secure space for constructing the first FOB.

“The airport had no activity at all,” Mwinga recalled.

Within days, they established a foothold and began pacifying the area.

“But within the first month, we patrolled aggressively and we could see the difference. Trucks, equivalent to our matatus, started ferrying passengers within three weeks.”

The subsequent month of aggressive patrols gradually revived a city where roads, markets and institutions had lain dormant under siege.

The seaport, also under gang control, was reopened after Kenyan officers cleared barricades and secured the inland transport corridor, allowing humanitarian cargo and commercial goods to flow again.

One of the mission’s defining moments came in Delmas, the stronghold of the notorious gang leader Jimmy Chérizier, globally known as “Barbecue.”

“So many missions had gone to Haiti, but we are the first to dislodge Barbecue from his hideout,” Mwinga said.

“We conducted targeted patrols and forced him out. Currently, we don’t know where he is… one day he stays; the next day he fears Kenyans.”

The operation earned the Kenyan officers unexpected admiration from residents, who, in fractured French and Creole, referred to them as “Kenyan our blood”—”Kenyans, our people.”

The early months were physically demanding.

Officers woke at 3:30 am daily, reporting to the Director General of the Haitian Police, equivalent to Kenya’s Inspector General, for briefings before heading out for patrols that often lasted until 9:30 pm.

“Most people were missing breakfast and lunch. That was the sacrifice,” Mwinga said.

The intensity of operations reflected the urgency of a nation in collapse, with armed groups controlling nearly every major government installation.

Among the facilities reclaimed by Kenyan forces was the Haitian National Police Academy, completely taken over by gangs.

By the time the contingent departed, the third cohort of Haitian police recruits was already in training.

The Armed Forces Training School, equally abandoned and unsafe, was restored.

“There was nothing happening, but as we speak, there are some recruits undergoing training, and that is the result of the people you are seeing here,” he said.

The national hospital, Haiti’s equivalent of Kenyatta National Hospital, had also been occupied by armed groups until Kenyan officers regained control, allowing medical services to resume.

The mission extended beyond Port-au-Prince.

After gangs massacred 100 people in the Artibonite region, about 150 kilometres from the main base, Mwinga said the contingent mounted a high-risk operation that restored calm and led to the establishment of two new FOBs.

With security restored, farming activities resumed in Artibonite, Haiti’s breadbasket.

“If you go there, it looks like Mwea. We ensured food was being produced to feed the people,” he said.

Throughout the deployment, the contingent operated under scrutiny from the United Nations and global human rights observers, particularly because past missions in Haiti had been marred by reports of sexual exploitation and excessive force.

Mwinga emphasised strict adherence to a code of conduct.

“For the 17 months we were there, there was no human rights abuse reported from the UN or rights groups. There were earlier cases of sexual exploitation in past missions, but we enforced zero tolerance. There is no single case involving our officers.”

Schools that had closed due to gang terror reopened and communities gradually regained confidence in public institutions.

The deployment, however, faced challenges.

Mwinga noted that the available armoured vehicles, MaxxPro carriers, lacked turrets and shooting ports, leaving officers vulnerable in urban combat where gangs operated from upper floors and hurled Molotov cocktails [a crude, hand-thrown bomb].

“That is what caused some casualties,” he said.

“The turret of the vehicle is open and fighting in built-up areas becomes very difficult. If those officers get the right armoured vehicles, it will be a game-changer.”

The 230 officers arrived in June 2024 under the Multinational Security Support Mission (MSS), now renamed the Gang Suppression Force (GSF), following the departure of a previous group.

“We left and told those we left there that we have set the pace. Continue,” Mwinga said.

Inspector General of Police Douglas Kanja announced that the returning officers will participate in the Jamhuri Day parade.

Kanja said this ceremonial march will recognise their service and reintroduce them to the Kenyan public.

“We want the people of Kenya to take note that you have gone to Haiti and you are back. You have been away for 18 months and you are now back,” he said.

“You will join that parade so that we tell Kenyans that these are our officers who have done the job there and are now back, sound, strong and ready to serve our motherland.”