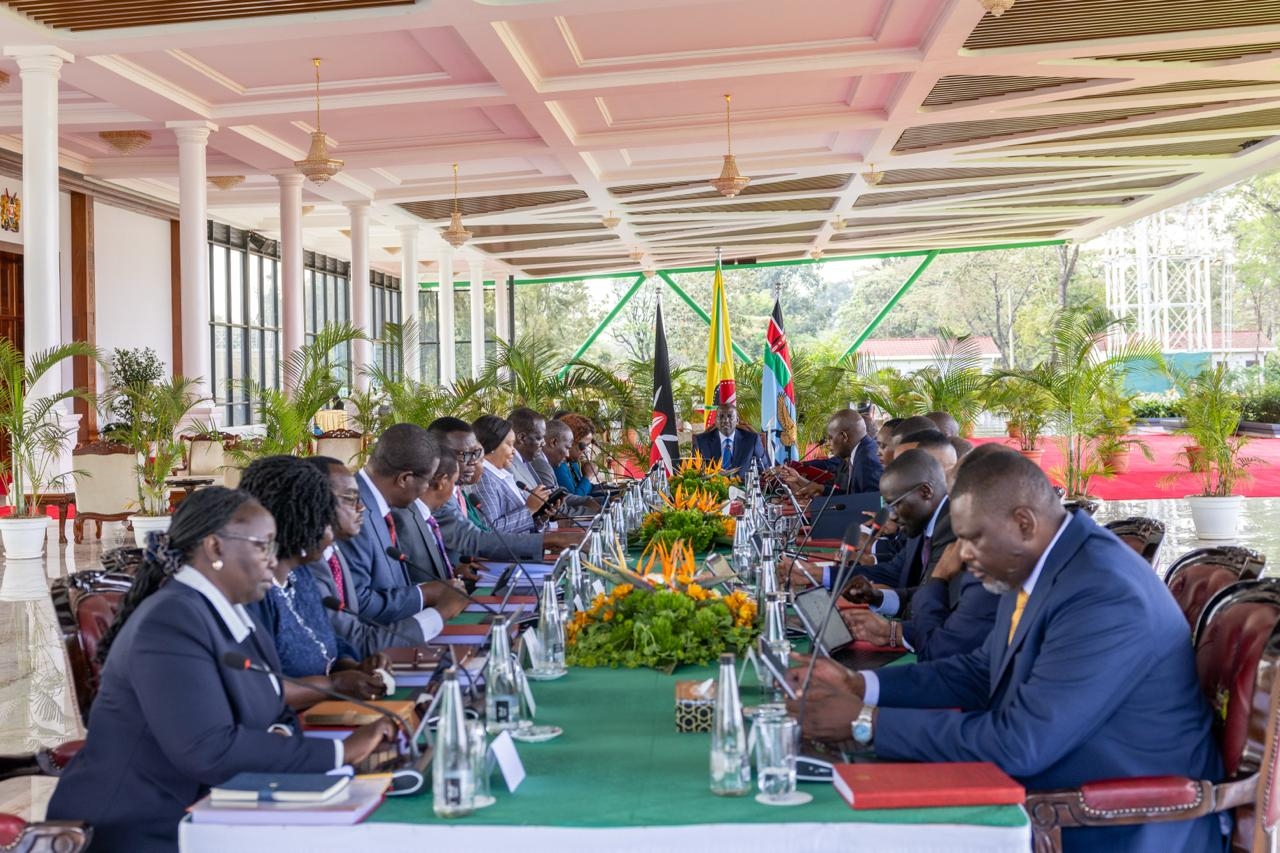

President William Ruto's handover of Amboseli National Park to the Government of Kajiado County, November 8, 2025./PCS

President William Ruto's handover of Amboseli National Park to the Government of Kajiado County, November 8, 2025./PCS

The transfer of Amboseli National Park from the national government to Kajiado County has stirred intense debate among conservationists, exposing deep divisions over the future of wildlife management.

While President William Ruto praised the move as “historic” and a triumph for community-led conservation, a section of conservationists fear it could open a pandora’s box—inviting other counties to demand control over national parks within their borders.

Carnivore ecologist Dr Mordecai Ogada, co-author of The Big Conservation Lie, was blunt in his criticism.

“It’s not wise at all. The Kajiado government doesn’t have the capacity to run a Class A national park,” he told the Star.

He warned that Amboseli’s pristine ecosystems could suffer under local management.

Others, however, see the transfer as an overdue step towards decolonising conservation and empowering local communities.

Environmentalist Steve Itela described the decision as “progressive on paper,” saying it recognises the constitutional spirit of devolution and gives communities a legitimate voice in managing natural resources.

“It could strengthen local ownership, improve response to human-wildlife conflict and integrate Maasai cultural stewardship into park management,” he said.

Itela said county-led conservation might even expand Amboseli’s reach through community conservancies and wildlife corridors, reconnecting fragmented landscapes.

Still, Itela cautioned that the shift raises “serious governance and policy questions”.

Without a clear national framework, he warned, Kenya risks fragmenting its conservation model, weakening the Kenya Wildlife Service’s coordination role and creating inconsistent standards across counties.

Jim Nyamu, director of the Elephant Neighbours Centre said, “You can’t just wake up and hand over everything. It’s a process.”

He called for safeguards and best practices to ensure the transition succeeds.

Nyamu said community-based conservation offers hope but warned that mishandling the process could embolden other counties to seek similar control.

During the handover ceremony on November 8, Ruto dismissed the scepticism, saying the move ends a 51-year dispute over the park’s management and restores stewardship to the Maasai community.

“This is not a weakening of conservation; it is a renewal,” he said. “Conservation led by the people lasts longer, works better and heals deeper.”

Ruto assured partners

that the Kenya Wildlife Service and the Wildlife Research and

Training Institute will continue providing security, ecological monitoring

and technical support, while the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife offers policy

guidance.

Set against the breathtaking backdrop of Mount Kilimanjaro, Amboseli is one of Kenya’s most iconic parks—home to vast herds of elephants, lions, zebras and more than 400 bird species.

It is a crown jewel of biodiversity and tourism, as well as a cultural treasure for the Maasai people who have coexisted with wildlife for generations.

As Kenya takes this bold step into community-led conservation, the world will be watching to see whether Amboseli becomes a model for devolution done right—or a cautionary tale of what happens when politics and preservation collide.

![[PHOTOS] Gor fans march to Bondo to honour Raila](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2F753aaa26-999c-40fe-bf2e-409fc6282745.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)