The 2010 Constitution says only a law must deal with the subject of a political parties fund.

The Bomas draft, in 2004, was very detailed. It required a fund with money provided each year by Parliament equal to not more than three per cent of the national budget for the preceding financial year.

The fund’s purpose was to cover the election expenses of the party and dissemination of its policies, organising civic education in democracy and the electoral processes, and not more than 10 per cent for the party’s administrative expenses. And the money was to be shared out: 30 per cent equally among the entitled political parties annually. Otherwise the basis was to be the number of votes secured by each political party in the previous National Assembly election, and the number of women candidates and marginalized groups elected through the party at that election.

Finally, a party that had not won at least one seat in the National Assembly or a devolved government for each of the two previous elections would get nothing.

This detailed provision largely survived till the Committee of Experts second draft in early 2010 (though with less detail on how the fund was to be used and distributed) and with the addition: “A party shall not be eligible for financial support from the Fund if more than two thirds of its registered national office holders are of the same gender”.

WHY POLITICAL PARTIES FUND?

Why should taxpayers’ money go to the running of parties and their campaigns at all?

Many countries do have some degree of public funding for parties. The justifications will be different, or differently emphasized, in different countries. In Kenya the idea forms part of the effort to build effective and well-run parties.

An element is no doubt the awareness that parties are generally unable to rely on members to contribute significantly to the parties’ expenses. In those circumstances parties (or candidates) will rely on people to fund them, and those people will expect some return, if the candidate is elected – jobs or contracts for example. A rather corrupt sort of arrangement.

Kenyan parties are generally unable to provide finance for their candidates’ campaigns, indeed expect candidates to pay substantial fees to be nominated by the party. This means that vying is very difficult for people who are neither wealthy nor able to raise money by this type of dubious deal. Public funding may make it possible for a wider section of society to stand.

Many countries want to be able to limit the involvement of the wealthy and the corporate sector (especially of foreigners) in elections in this way. They may want to ban some other people from contributing to parties. Or they may want at least to require that the sources of donations are made public. It is easier to demand these, if there is a public funding.

It often seems a good idea to try to reduce the impact of money in elections by setting a maximum that parties or candidates may spend on campaigning.

Similarly it may be easier to demand that political parties’ financial dealing are properly audited if there is a public element in them.

And using public resources in other ways is generally banned or severely limited – and maybe having an official form of public funding makes this more acceptable.

We can see some of these linkages in the Kenyan context. The Bomas draft said, “Parliament shall specify sources from which political parties shall not receive subscriptions, donations or contributions; and the maximum donation that an individual or an institution or body can make to a political party.”

The funding may be used as an incentive – parties may only be entitled, if they are democratically run, and they may receive more money if, for example, they have managed to get more women, or minorities, elected.

Finally the risk of people setting up parties just to get access to public funds must be avoided. So usually parties must have shown some degree of success in elections before they are entitled to public funding.

KENYAN REALITY

Parties, and politicians, definitely want public funding, but they want to set the criteria. All the detail in the CoE draft constitution disappeared in Naivasha, when the committee of MPs got their hands on the draft.

When MPs did come to make law they fixed a minimum (rather than a maximum) - at least three per cent of the money collected by the national government. That was a lot – not so far short of the equalization fund intended to bring marginalised areas in counties to greater equality with the rest of the country.

They also provided that only big parties would get the money. They did not put it quite like that – but that a party would only get anything from the fund if it had received at least five per cent of the total votes at the preceding general elections. And that was at least five per cent of all the votes cast in the elections for the President, members of Parliament, governors and MCAs.

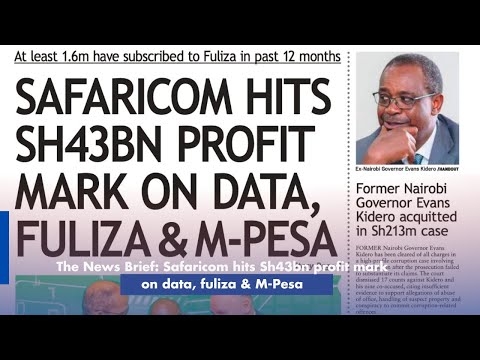

When you consider that very few parties put up candidates for President, and that in 2017 Uhuru Kenyatta (Jubilee) and Raila Odinga (ODM) between them got 99 per cent of the presidential vote, is it surprising that, for example, only those parties got any of the Fund after the 2017 elections?

In addition, for a while, the law excluded any party that had not got a considerable number of specified office holders from getting any of the fund.

They quite “forgot” about the gender and minorities issue in the original Act. Distribution of the Fund between parties took no account of how many women or minorities had been elected on the party ticket. But they did allow that the money could be used for “promoting the representation in Parliament and in the county assemblies of women, persons with disabilities, youth, ethnic and other minorities and marginalised communities.” But no more than 25 per cent could be spent by a party on this. It was the only type of expenditure of the Fund by a party that had a ceiling placed on it. Later they amended the Act to say that 15 per cent of the money should be allocated on the basis on how many members of special interest groups had been elected (no requirement that this must, for example include women).

They did prevent financial assistance from foreigners, forbid any individual or group to contribute more than five per cent of the total expenditure of a party in a year, and require parties to file details of their courses of revenue each year with the Registrar of Political Parties.

RECENT DEVELOPMENT

In 2022 the law was again changed. Now a party must have at least one elected MP, elected senator, a governor; or an elected MCA – however many votes they got. This is much less than the early requirements about having certain specific elected members. But so long as the sharing is based on the number of votes cast, including for the president, big parties will be very advantaged. And – unlike the Bomas draft – there is no amount shared equally among entitled parties. Small parties are unlikely ever to get significant funding, so levelling the playing field is not part of the project.

Parliament deleted the requirement for parties’ accounts to be audited by the Auditor General.

Last year the National Assembly rejected limits on campaign expenditure included in regulations prepared by the IEBC. They had procedural objections – but do they really want limits on spending?

What are the chances of public funding fulfilling its purposes in Kenya? Parties form around individuals, and disintegrate when rival leaders can’t be accommodated. It seems the possibility of funding is unlikely to affect this process. A party that receives the money may be very different from the party that “earned” the money.

And the parties may love the money but not the corollaries of transparency, accountability, limits of spending and generally trying to make money less central to politics.