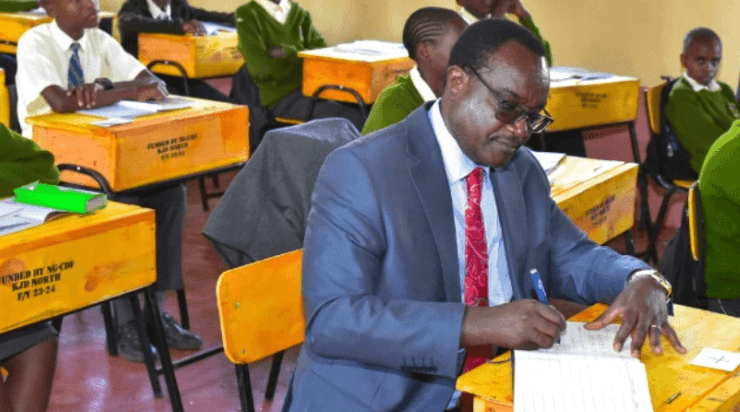

Farmers taking stock of their spices produce at a farm in Nakuru. /HANDOUT

A proposed law seeking to enforce foreign firms to source 60 percent of their raw materials locally and ensure 80 percent of their workforce is Kenyan has sparked anxiety.

The Local Content Bill, published in October 2025 has placed government, farmers, manufacturers and multinational firms on a collision course, ahead of the proposed October 2026 implementation date.

If it becomes law, non-compliance will attract a minimum fine of Sh100 million and possible jail terms of at least one year for CEOs.

While the bill aims to boost farmers, stimulate local manufacturing, and create jobs, stakeholders warn that the legislation may backfire, arguing that it discriminates against multinationals, risks deterring investment, and demands capacity that many Kenyan farmers are yet to attain.

British consumer goods giant Unilever, which has spent four years raising its local sourcing from 30 to 70 per cent, says the bill while well-intentioned is unrealistic and unfairly targets foreign firms.

“As currently crafted, it will end up being a disadvantage for industry, especially for ourselves, it seems that there are going to be barriers being put for us as a multinational that are not applicable to other organisations being called local. That seems discriminatory,” said Unilever East Africa managing director Luck Ochieng.

Ochieng added that the bill could undermine Kenya’s competitiveness, warning that meeting 100 per cent sourcing requires extensive investment in training, aggregation, and financing costs not faced by local competitors.

“For us to reach 70 per cent local sourcing, it has taken a lot of investments. It is possible to get to 100 per cent, but it requires far more investment and a significant expansion of the farmer base.”

Project manager at Njoro Canning Factory, Evanson Njuguna said that the deadlines in the bill are too ambitious.

“It would be reasonable to bring the bill to action after five years. We feel it is too ambitious, as these projects will take time to onboard farmers to produce in the required volumes,” said Njuguna.

The factory works with 2,000 contracted farmers supplying coriander, chilli, and other crops, but Njuguna says farmers still need extensive exposure, training and support to meet multinational standards.

“Most of the farmers doing spices are new, but we are picking up. The experience is the farmers would like more exposure, more training, more benchmarking, and also to have more technical understanding of the material,” Njuguna added.

From the engagements, road access, literacy levels and crop quality remain persistent challenges, particularly during rainy seasons.

Smallholder farmers also echoed similar concerns, Alex Okello, a farmer from Nakuru County who supplies sweet corn and coriander to the factory said that they currently rely on training from the multinationals they are supplying to access seeds.

“Sweetcorn costs Sh100,000 per acre and coriander Sh30,000. If weather and irrigation hold, we walk into profits,” he said.

But farmers like Okello still depend heavily on factory support, seeds, extensions officers and guaranteed markets to meet quality demands.

The stakeholders pointed out that for crops like cumin, which do not grow naturally in Kenya, the bill’s requirements may be impossible.

“Some spices we require do not naturally grow here and need to be imported,” said Vipul Patel, a director at the company “Farmers may struggle meeting demand and standards for crops like cumin.”

Stakeholders say the bill, in its current form, risks creating winners and losers, empowering some farmers while pushing some manufacturers and multinationals to scale back operations.