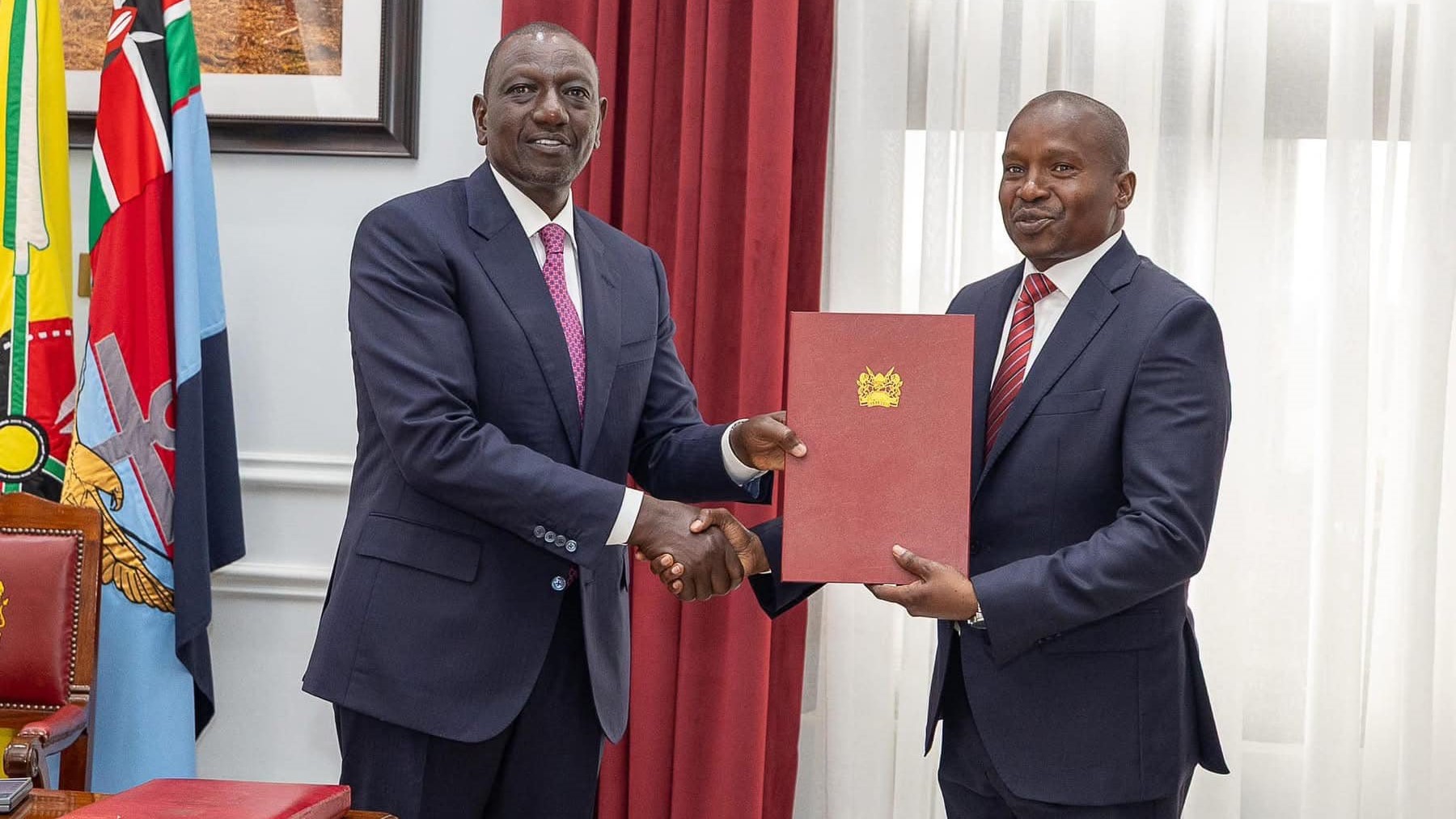

The most recent example is the fractured relationship between President William Ruto and his former deputy, Rigathi Gachagua. The fallouts between Kenya’s presidents and their vices/deputies can be traced back to the first post-colonial administration whereby the country’s first Vice President Oginga Odinga parted ways with his boss, President Kenyatta two years into their political union.

Other cases include the fall-outs between the second vice president Josephat Karanja and president Kenyatta, Daniel Moi v/s Kibaki, Moi v/s Saitoti and president Kenyatta II v/s D.P William Ruto.

Whereas many reasons could be cited for the fallout, two are clearly observable and cutting across all the cases mentioned above — power dynamics and succession politics. Most number twos feel entitled to an equal treatment with the president as a reward for their investment (financial and political) into the president’s victory.

Such a scenario played vividly when the relationship between President Ruto and Gachagua became shaky and eventually irreparably damaged. It is alleged that Gachagua demanded to be paid Sh8,000 for every Mt Kenya vote as compensation for rallying support for the President in the vote rich Mt Kenya region.

The tension between Gachagua and Ruto began when the opposition chief Raila Odinga began to edge closer to the President in February 2024, leaving Gachagua feeling sidelined. In the presidency, Gachagua is also allegedly accused of making demands for billions of monies to push for several development projects in the Mt Kenya region as well as turn the DPs residence into a castle.

When the President renovated State House, Gachagua demanded a hefty budget for him to do the same to his residence. He also allegedly demanded for his confidential vote to be added to his budget. All this point out to one thing – the DP feeling entitled to treatment equal to the President. Why? Did he see himself as a co-president? Perhaps yes.

Another fall out still fresh in Kenyans’ minds is that of Ruto (then Deputy President) and his boss President Uhuru Kenyatta. This began to materialize when Kenyatta and Raila had the famous “Handshake” of January 2018, which brought the opposition into government. The DP felt that his powers had been diluted with him remaining as only a ceremonial figure.

The second reason why Kenya’s presidents have been falling out with their deputies is succession politics. This is seen in the case of Moi v/s Saitoti whereby the former chose to discard the later, opting for Uhuru as his choice for the 2002 presidential polls.

Political pundits opine that Moi had to elbow George Saitoti out of the inner sanctums of power to make his ascension to the presidency impossible since he wanted to give the Kenyatta family a ‘kick back’ by endorsing Uhuru.

Saitoti, after being unceremoniously fired and ridiculed by the President, joined the Rainbow coalition and vehemently campaigned for Kibaki who emerged the winner.

In the run up to the 2022 elections, the already soiled relationship between Uhuru and Ruto was worsened by the President’s announcement that he would not be backing his deputy for the top seat. Instead, Uhuru backed Ruto’s chief rival Raila.

Their ‘political enmity’ would soon hit the climax as they openly started to make all manner of accusations against each other for the failures of the Jubilee government. All the other cases have been more or less of the same.

LAW CHANGE

The quest of entrenching two or more deputy presidents in our Constitution would cure the two challenges highlighted above in that one, it would be clear to the DPs from the onset that a deputy is in no way equal to the president.

Two, having more than one deputy president, each representing a significant political bloc, would create a more inclusive Executive, ensuring that no single ethnic group can lay claim to half of the government’s resources or positions.

This would curb the current practice where a deputy president, feeling responsible for delivering a substantial voter base, demands disproportionate power or resources.

Additionally, multiple deputy presidents would help neutralize succession politics. If there were two or three deputies, none would automatically assume they are the president’s heir, nor would the president be pressured to endorse any particular deputy.

This approach would discourage bitter fallouts, especially towards the end of a president’s tenure, when succession politics typically destabilize administrations. By eliminating a singular successor, Kenya’s presidents could govern more effectively without the political distractions of grooming a replacement or dealing with insubordinate deputies positioning themselves for power.

Kenya would not be an outlier in adopting such a system. Sudan, during Omar al-Bashir’s presidency, had two vice presidents—Ali Osman Taha representing Northern interests and Al-Haj Adam Youssef— representing Darfur and other marginalized areas.

Tanzania, before its 1995 constitutional reforms, had multiple vice presidents, with the President of Zanzibar being recognized as a vice president of the United Republic of Tanzania. Afghanistan also employed a similar model under Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani’s governments, with two vice presidents ensuring diverse political representation. These examples demonstrate that a multi-deputy system is both feasible and beneficial in managing diverse political landscapes.

In light of this, it is now clear that Kenya is ripe for constitutional reforms to diffuse power struggles, ensure broader political representation, and prevent the entitlement mentality by ethnic communities and some political elite that often leads to governance paralysis.

Benjamin Musyimi is a political writer based in Nairobi