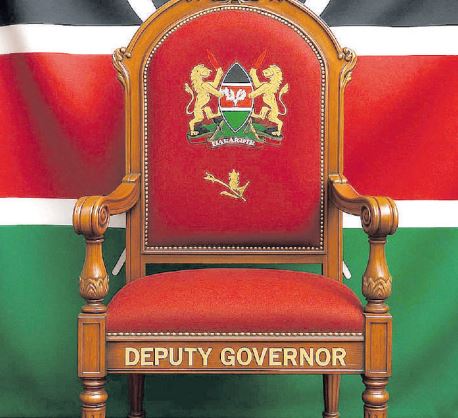

You may have read about county governors having bad working relationships with their deputies. Indeed, the relationship between them often deteriorates soon after elections, sometimes threatening to cripple the running of counties.

Some are reported to even scheme to impeach each other. For instance, there is some indication that the governor instigated the very first impeachment of a deputy governor (in Kisii county).

A year later, the key witness reportedly sought to retract his testimony, claiming that the governor coerced him to accuse the DG falsely.

You may wonder how two people who agreed to work together, spent months campaigning together and got elected together suddenly cannot stand each other. The answer to this question depends on who you ask.

For governors, it is about DGs failing to understand their roles as principal assistants and wanting to be treated as “co-governors”.

According to them, DGs don’t know their place and have poor interpersonal skills. For DGs, the failure lies in the law not specifying what they should do in the day-to-day running of the county.

This, they argue, subjects them to the unchecked discretion of the governor, who decides what they will do and whether they get any funding for their offices. But what really is fueling the infighting between these two?

The simple answer is power. One is preoccupied by the fear of losing it and hence hoards it, and the other is motivated by the possibility of gaining it hence angles for it.

For governors, the DG is the greatest beneficiary if anything happens to them and is a leading contender for governorship in the next election.

For DGs, they stand to benefit immensely if the governor leaves office and their position provides the best launching pad for their gubernatorial ambitions.

In truth, DG candidates are chosen to attract voter support rather than because the governor candidates feel they could work well together.

WHAT DOES THE LAW SAY?

The constitution recognises DGs as county deputy chief executives and as members of county executive committees (CECs). It says a DG will act as county boss when the governor is “absent” and become governor if for any reason the governor is no longer in office.

However, it says nothing about what the deputy governor should do day-to-day.

IS IT LIKE THE DEPUTY PRESIDENT? The constitution provides a little more detail about what a Deputy President should do. In addition to recognising the DP as a Cabinet member, it designates him/her as the President's principal assistant and requires him/her to deputise for the President in the execution of the President’s functions.

It requires the DP to act as President when the head of state is temporarily incapacitated or is absent. The DP is also required to take over whenever a vacancy occurs in the office of the President.

The constitution confers discretion on the President to assign the DP additional roles beyond those given by the constitution.

It also allows the President to decide any other times when the DP may act as President. In addition, Parliament has assigned the DP the role of chairing the Intergovernmental Budget and Economic Council (IBEC) under the Public Finance Management Act.

IBEC serves as a forum for canvassing and resolving money-related issues between the national and county governments. Taking a cue from this, Parliament sought to provide more detail to the DG’s role through the County Governments Act.

Under the Act, the DG deputises for the governor in the execution of the governor’s functions. Presumably, the DG deputises if the governor asks him/her to.

The governor is also given discretion to assign the DG any other responsibility or portfolio as a member of the CEC. Even with this, the role of the DG in the everyday running of the county wasn’t (and isn’t) clear.

According to the Deputy Governors’ Caucus, only about seven governors have exercised the discretion to assign functions and have a working relationship with their DGs.

This means that up to 40 DGs continue to draw monthly salaries despite not having and/or performing any specific roles.

PARLIAMENT’S PROPOSAL

To address this issue, Senate Deputy Speaker, Kathuri Murungi, has proposed the County Government Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2024. The Bill proposes to amend specific parts of the CGA and the Intergovernmental Relations Act.

The Bill appears to adopt the DGs’ perspective on the problem, which explains its total rejection by governors. Its solution focuses on assigning specific mandates to DGs under the law.

In other words, the Bill’s drafters believe that tying the governor’s hand or dictating in mandatory terms how he/she exercises discretion in assigning the DG roles would cure the infighting.

THE PROBLEM WITH PARLIAMENT’S PROPOSAL

Some of the listed functions overlap with the functions of the governor. Some overlap with those of the CEC member for finance. “Deputise for” cannot surely be interpreted to mean “take over”. Without clarity, therefore, these stand to be a source of further conflicts.

The Bill also allows the governor to make the DG a CEC member with a portfolio. This undermines the DG’s constitutional role as the governor's principal assistant. Besides, will other departments receive equal treatment to that headed by the DG? What happens when the DG has to act as governor?

Assigning most of the DG’s functions in mandatory terms is highly problematic. It undermines executive discretion critical in facilitating flexibility, adaptability and the efficient administration of the county.

This discretion is clear from that given to the President to assign roles to his/her deputy. Taking away discretion is more likely to worsen conflicts and stall county service delivery.

WHAT OPTIONS ARE AVAILABLE?

Article 200 of the Constitution gives Parliament the power to make laws to implement devolution.

The Bill is therefore a step in the right direction. Similar to the DP’s legislative role of chairing IBEC, the DG may be given some specific functions under the law. However, this should be kept to a minimum so as not to interfere with the DG’s constitutional role as principal assistant or the DG’s ability to represent the governor or act as governor.

They should also not conflict with or undermine those of the governor or any other county department.

The assigned roles could include presenting reports on behalf of the CEC to county assemblies and chairing committees and sub-committees of the CEC as is the case with some lieutenant governors in the US.

The Bill could also help by clarifying when the DG can act as governor. What is absence? When can a governor be said to be absent? Can a governor be present by Zoom? The High Court has recommended that Parliament provides this clarification.

It is not an easy task. Executive discretion is vital for effective administration. However, its exercise can be made accountable without tying the governor’s hands and crippling county administration.

For instance, some functions can be listed as those which the governor may assign to the DG. These can then be followed with a requirement for the governor to report in the annual report to the Assembly on the steps he/she has taken to implement this.

An extreme option that would address the underlying political interests would be to limit the right of DGs to vie for governorship immediately after their term as DG.

This should not prevent them from vying for any other political seat. Perhaps this may remove the political threat to the governor and make him/her open to effectively working with the DG.

The challenge with this, however, is that it would limit political rights under Article 38. Political rights are not absolute and are limited in various ways under the constitution itself. But new limits would need to pass the stringent test under Article 24 of the constitution.

The writer is the Devolution and Research Lead at Katiba Institute.

![[PHOTOS] Tears as ODM leaders visit Were's rural home](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F05%2F08d9d767-4e03-45fb-8dde-0ca0d13c5c64.jpg&w=3840&q=100)