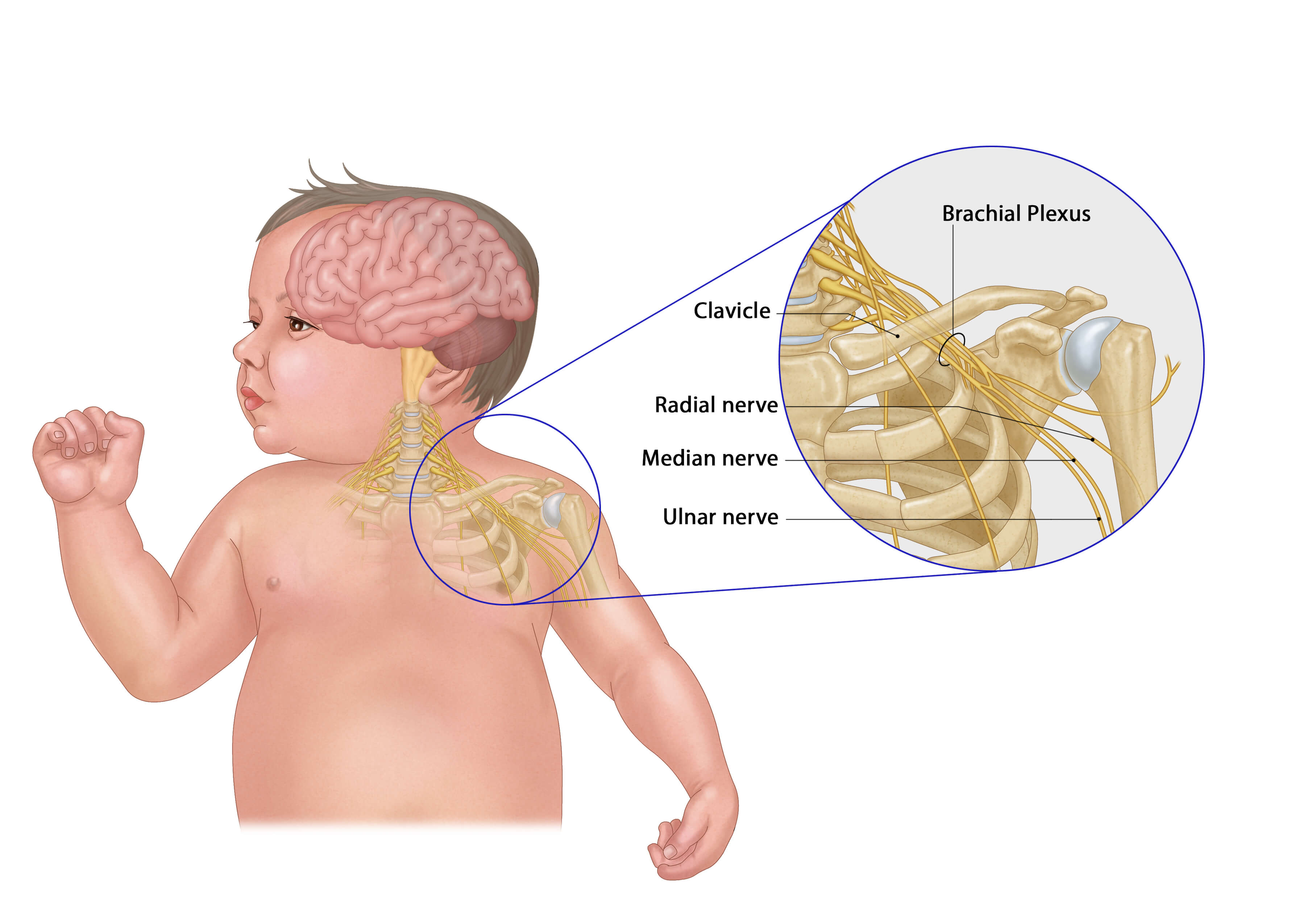

A photo showing a baby with a birth brachial injury

A photo showing a baby with a birth brachial injuryBirthing is a delicate process suspended between hope and uncertainty. This moment calls for the medical personnel to be extra careful. Possible complications

are not just limited to the mother; infants also face imminent danger.

Among these dangers is Birth Brachial Plexus Palsy (BBPP), a

condition that can rob a child of movement in their arm. It can

render a tiny limp to never move, turning what should be a milestone that brings joy into frustrations and sometimes tears.

Dr Dorsi Jowi, a consultant plastic and reconstructive surgeon and hand specialist, was the lead surgeon during the first successful BBPP surgery at the Kenyatta National Hospital on a four-year-old girl recently.

She explains the brachial plexus as a network of nerves

that supply the upper limb. She says that it comes from the upper part of the

spinal cord, in the neck and gives both movement and sensation to the arm.

In birth brachial plexus injuries, these vital nerves are

stretched, ruptured or even torn away from the spinal cord, most often during

the birthing process itself, particularly if the delivery is complicated or the

baby is larger than average.

She says: “The majority of the causes are

usually difficult labours, especially with bigger babies, whereas the baby

passes through the birth canal, the neck and shoulder might be pulled in

opposite directions. This causes a traction injury to the nerves.”

She says that this type of injury may present itself

immediately at birth. She notes that with brachial plexus injuries, you will

notice almost immediately that the baby is not able to move their affected limb.

An observant paediatrician or parent may notice one arm remains motionless or

held unnaturally close to the body while the other moves freely.

While the diagnosis is often immediate, the road to recovery

is more complex. “Surgery is not always done at birth. Our first job is to

assess the child and find out which level of the brachial plexus has been

injured,” Dr Dorsi notes. “Not all injuries require surgery, and about 80 per cent will recover, although that recovery is rarely full functional recovery."

The surgical decision depends upon the type and extent of

nerve damage, which may be: Neuropraxia, which is stretching with no actual

severing of the nerve and usually heals with therapy alone; Rupture, where the

nerve is torn but still attached to the spinal cord; and avulsion where the

nerve is completely torn away from the spinal cord.

“In cases of rupture, surgery may involve finding the two

ends and directly repairing them. If the gap is too wide, we use a 'nerve

graft'—borrowing a nerve from elsewhere in the body to bridge it,” Dr Dorsi

explains. For avulsion, where direct repair is impossible, surgeons may perform

a “nerve transfer” using donor nerves from other areas.

On treatment, Dr Dorsi says that it is a multidisciplinary path.

“It is always a team approach,” says Dr Dorsi. “We work alongside

physiotherapists, occupational therapists, paediatricians and neurologists.

Selecting a procedure depends on factors like the type of injury, severity and

how much function is returning over the first few months.”

She says that surgical intervention is usually considered

between four and nine months of age if there’s no meaningful recovery. “The

earlier we do the surgery, the better the outcomes, but even at two or four

years old, we may still help by releasing tight muscles or performing

additional operations,” Dr Dorsi adds.

While nerve surgery can never offer a 100 per cent guarantee, the

potential for life-changing improvement is real.

“One of the main improvements is the ability to lift the

shoulder and bend the elbow. That alone transforms what the child can

do; it means they can reach, grab and do activities that would otherwise be

impossible,” Dr. Dorsi says.

She says families can expect functional improvement

of 80–90 per cent, particularly when diligent post-surgical physiotherapy is paired

with the operation. She adds that recovery is never ‘full function,’ but

physiotherapy and consistent care can make an enormous difference.

Dr Dorsi, however, says that not all children with BBPP

require surgery. For milder injuries, physiotherapy is key. Stretching and

exercising the limb helps maintain flexibility in joints and strength in muscles.

Even children who undergo surgery need ongoing non-surgical management to increase

function.

Despite the technological advancement, this surgery still

has its barriers. “The surgery itself is costly and lengthy, often taking about

six hours. The specialised equipment, the surgical expertise and the need for a

pediatric anesthesiologist all make it more expensive. In Kenya, there are

currently only two or three specialists trained to do this kind of surgery."

Late referrals and lack of awareness among both the public

and healthcare providers mean many children simply miss the window when surgery

is most effective.

“We want families and professionals to know there is an

option for nerve surgery in infancy that can make a huge difference. If you see

a baby with this condition, refer them to a specialist early,” urges Dr Dorsi.

For families facing this daunting diagnosis, the path ahead

requires courage, commitment and hope. With the advancement in surgery and the

dedication of interdisciplinary teams, many children affected by birth brachial

plexus palsy can look to the future with hope that it can be corrected.